On October 15, 2017 I got the amazing opportunity to travel on SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy. My University of Washington advisor, Emily Levesque, proposed to observe the dust of massive red supergiant stars using FORCAST, a mid-IR camera and spectrograph. My long-time collaborator Phil Massey was a co-I on the proposal and they both agreed to take me on the flight if we were awarded time. A few months ago we heard that the proposal was successful and Phil and I signed up for a flight in mid-October (Emily traveled down to New Zealand a few months ago to observe some of the southern hemisphere targets).

SOFIA in all of its glory on the Palmdale tarmac awaiting take-off.

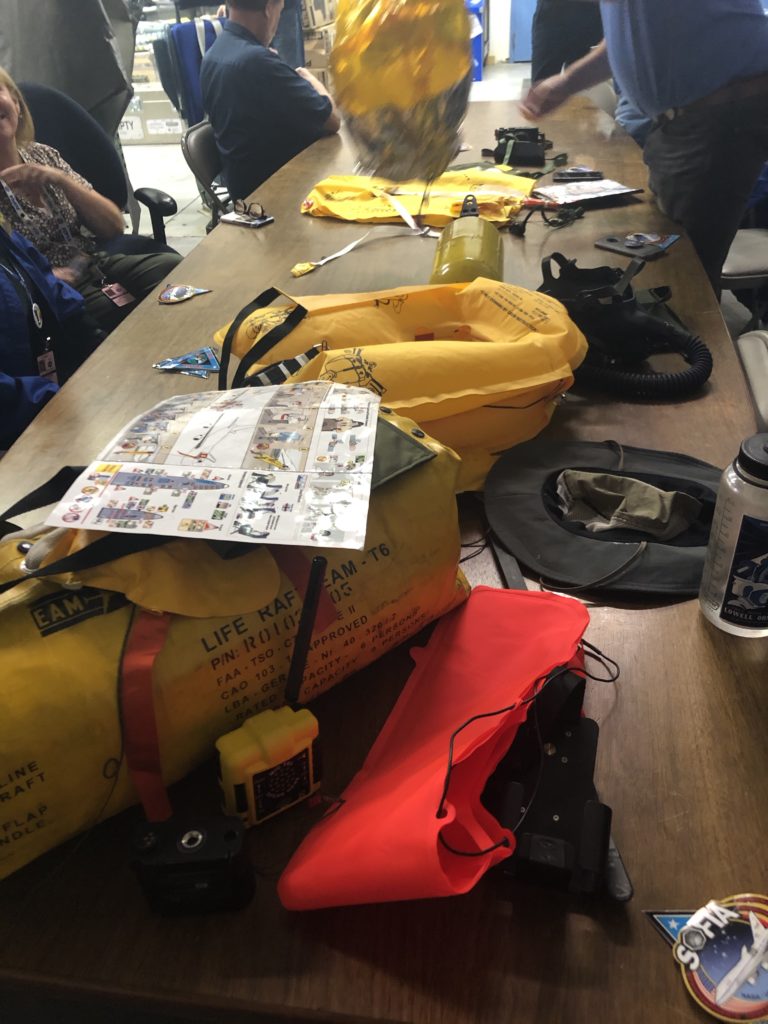

Most of the year SOFIA flies out of Palmdale, CA so Phil and I met up in LAX and drove to Palmdale (with an In-N-Out stop on the way). The next day we arrived at the NASA building for orientation. First was “egress” training where we learned about how to deal with emergencies on SOFIA. While many of the standard airline safety features applied, there were a few additions. For one, we were up and walking around for a lot of the flight so in case of cabin air-pressure loss, we all had our own little portable oxygen masks that we carried around with us. Additionally, we learned how to exit the plane from the cockpit (you basically grab a rope, open a door on the top of the plane and jump … wheeeeee), and deploy the slides (if you hold onto the door for too long it will pull you out of the plane when it opens … fun?). After egress training we learned a bit about the science goals of the night and then headed off to the mission briefing where all 27 people who were going to be flying that night discussed the status of the airplane (good), telescope (good) and instrument (not sure … but someone thinks they saw it on the telescope? maybe?). A meteorologist also gave us an overview of the weather on our flight route. After that it was almost time for take-off!

Playing with all of the life-saving emergency equipment during egress training.

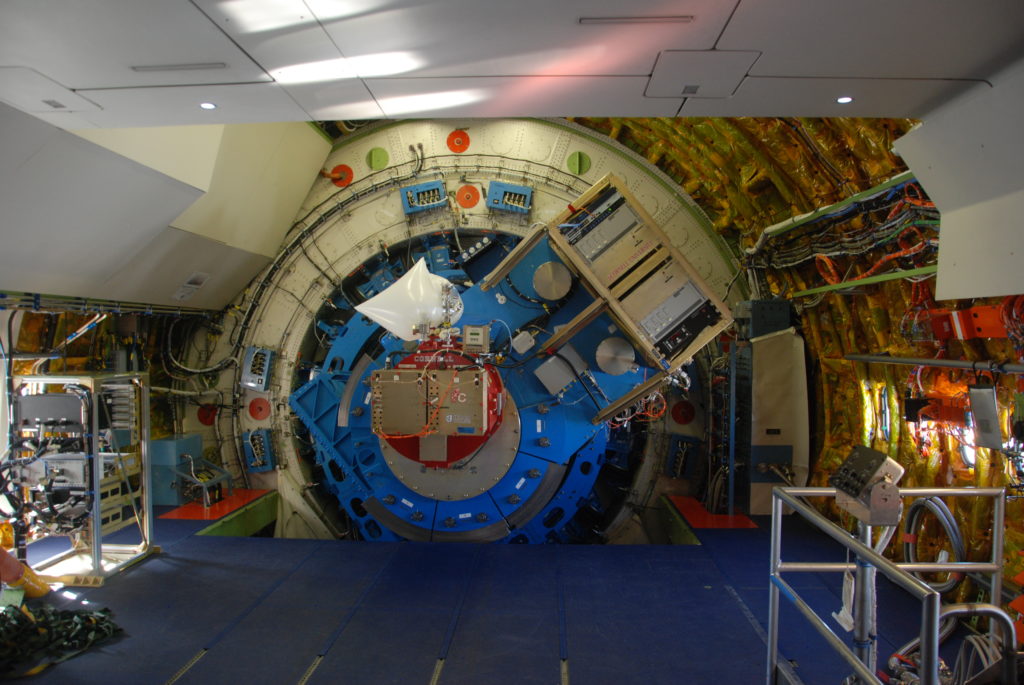

The layout of SOFIA can be broken up into segments. At the very back of the plane is the telescope. As someone pointed out to us, it was an interesting design decision to put an IR telescope behind the engines. But, as time has shown, it appears to work! Because the telescope weighs so much (tons!), there is a large counterweight in the front of the plane to keep the center of gravity where it would be in a more “normal” 747. To cut down on weight, most of the plane’s insulation has been removed. This leads to very noisy and very cold flights (more about that later).

Telescope mounted at the back of the plane. The red box is FORCAST, the instrument.

In the middle of the plane is where the bulk of the people sit. The first row is comprised of the instrument and telescope operators. They keep track of the pointing of the telescope, the observations, etc. A few of them had been telescope / instrument operators at ground based observatories before arriving at SOFIA and they said that in may ways the operating procedures are quite similar … except for the flying part. The next row has a table for the “scientists” to sit at and the two consoles for the mission directors. The mission directors keep everything on schedule and act as the “go-betweens” for the pilots and everyone else on the airplane. They also, as we discovered, have the very important job of yelling at everyone to sit down when the seat belt sign comes on and then reminding the pilots to take off the seat belt sign when they eventually forget.

Middle of SOFIA.

Next is the “overflow” scientist table (complete with two chairs that have been deemed “unsafe” for take-off and landing) and the educator’s consoles. SOFIA has a big education component and people from the media, high-school teachers, public-program educators, etc. are often invited on the flights. In the nose of the plane are the “first class” seats where people can go to get work done or sleep. Finally, upstairs is the cockpit and a few more comfy chairs.

First class seats and stairs to the upper level / cockpit.

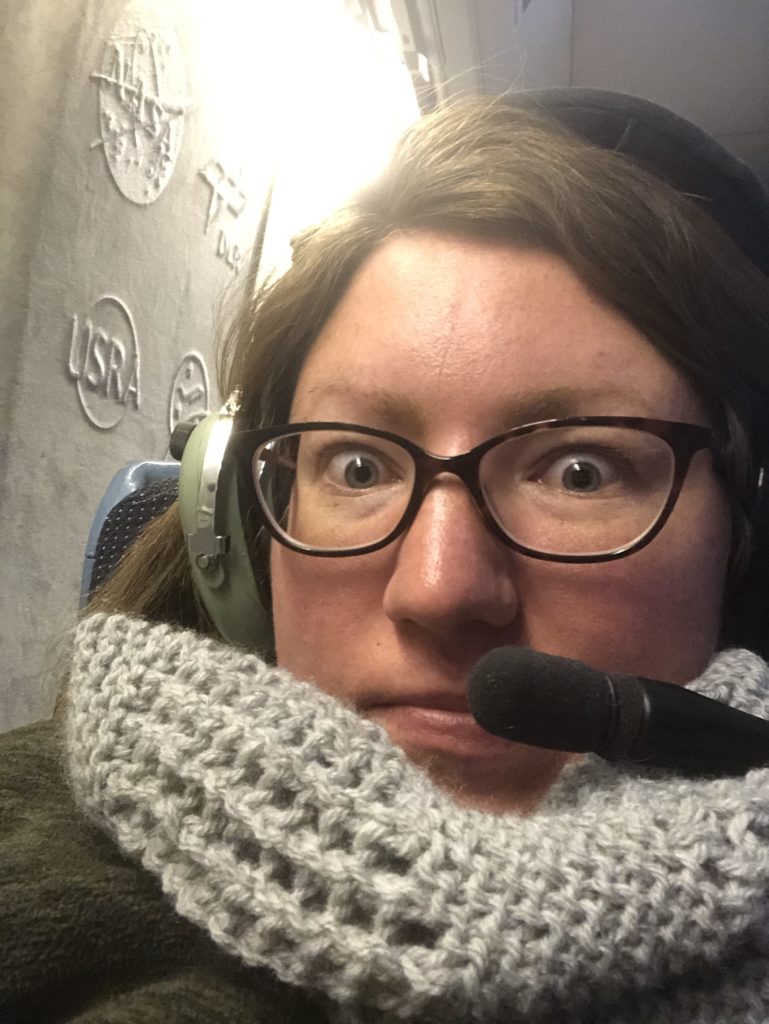

As I mentioned above, SOFIA is both very loud and very cold. Due to the nose, everyone is encouraged to either wear ear plugs or headphones. The provided headphones plug into the plane’s audio system and allow you to listen to and speak with everyone else on the plane. Each “group” has their own channel (mission directors, scientists, educators, telescope and instrument specialists, etc.) and it is possible to select which channels you want to listen to or talk on throughout the flight. My personal favorite channel to listen to was the flight deck (aka, the pilots). On this channel you could hear the pilots talk with the various control towers and each other. As Phil said at one point, “if you don’t think about it, you can almost convince yourself you’re on a very loud subway.” Listening to the flight deck reminded me that we were up in the air flying a crazy route around the Western US.

Me listening to the flight deck … and also being cold and tired.

The telescope on SOFIA points in one direction: out of the plane. This means that if you want to look at an object, you need to be flying perpendicular to it. So, the flight paths for SOFIA are very amusing. We started off from Palmdale, flew towards Tucson, then Albuquerque, then up to Denver, Salt Lake City, back down to Denver and Albuquerque, over to Texas, back up towards Denver, over towards Phoenix, back towards LA, over Palmdale (wave!), up to Las Vegas, and then back to Palmdale … all in 10 hours. Every time we re-entered Denver airspace the flight controller would laugh and say “welcome back!” SOFIA also flies much higher than a normal commercial aircraft - we averaged between 41,000 and 43,000 feet throughout the night. This decreases both the turbulence and the amount of water vapor that we’re observing through.

My favorite part of the experience was getting the opportunity to fly in the cockpit and talk with the pilots. The SOFIA plane was built in 1977 and still has much of the original 1977 flight control system. While some things were upgraded in the 90s and early 2000s, most of the buttons remain. There is additionally the need for a flight engineer (plus the pilot and co-pilot) to watch all the buttons and switches in the back. As someone who does a lot of flying, being able to sit in the cockpit and watch the pilots control the plane was really amazing. It was a little disconcerting how small the windows were and how little you could see out of them (it was night, and the lights were on), but I guess that’s what auto-pilot is for …

The cockpit of SOFIA … basically a 747 from 1977.

As the resident scientists on board, we did very little (and even that is an understatement). All of the observing times are meticulously planned in advance so there is little room for deviation throughout the flight. Additionally, we found out a few days before our flight that our science targets (the red supergiants) had been bumped to another flight. But, because we already had reservations, we decided to go anyway. While it would have been cool to see some red supergiant IR spectra read down, there wasn’t much we would have been able to do with it other than say, “oh! nice! looks good!” BUT, we still got to observe something pretty special … the moon!

Trying to get positioned correctly on the Moon.

On board with us were a group of three University of Hawaii graduate students who had applied for SOFIA time to look at the moon in search of water. They had previously successfully detected it using SOFIA last year and were back to look in other places. Now, it turns out that observing the moon with SOFIA is actually quite difficult. For one, the moon is moving … it isn’t like a star with a singular right ascension and declination value. So, they had to track at the moon’s tracking rate instead of sidereal. Also, the moon is bright! Last year they observed the moon in the middle of the night and ended up saturating the chip so much that it left a residual moon imprint for the next few exposures. So, this time the moon observing was left until the end of the night. But, what proved to be a real issue was sky subtraction. IR-observing uses a method called “nod and shuffle” to obtain data both on and off the target that can later be used for sky subtraction (because the sky is really bright in the IR). With a point source, it is pretty easy to quickly move the telescope away from the target, take an image, move back to the target, take an image, and repeat. But, the moon is big! And still bright! Thus, they discovered that it was difficult to move far enough away from the moon during the nod and shuffle routine and avoid getting stray moon-light on the detector. They had allotted 30-ish minutes to observe the moon and ended up asking the pilots for a 2 minute extension. It was requested, and they were able to get around 1.5 minutes worth of data for the University of Hawaii grad students. Luckily the moon is bright so the spectra was well-exposed and hopefully it will be what they need!

Everyone looking at the incoming Moon data.

After 10 hours of flying, we landed back in Palmdale at around 6:30 am. It really was an amazing experience … I mean, how often do you get to fly in an airplane with a telescope sticking out of it? Now I need to see if American Airlines will give me some frequent flyer miles …

Sunrise on SOFIA.